By Laurence Lee Shanghai Singapore International School

Inquiry-Based Learning (IBL) and Project-Based Learning (PBL) are two frequent buzz words used in education today. The IB recognises the importance of developing students’ research skills, critical thinking skills and creative thinking skills, as do many of the world’s leading curriculums.

PBL and IBL are used in a variety of classrooms in a variety of forms. What they look like and what benefits they bring to the classroom are often the subject of debate. Once we’ve decided to take the leap and implement PBL into our classrooms, what’s next? How can we scaffold student learning and structure the process for students successfully?

The good news is, whether you are running a project-based learning module in a classroom of Middle School students, or guiding students through the early stages of the IB Extended Essay, there is a scaffolding model that can be used to make the process more structured. It can be used in a variety of situations and is particularly useful when there is an element of research or inquiry involved. One of the benefits of using this scaffolding model is that thinking skills are explicitly developed along the way. In fact, the scaffold is structured around how students think about the information they are handling in any given classroom task.

Implementing a Research Project Scaffolding Model

So what we are looking at is really a thinking skills model, that can be applied to research projects, amongst other things. Before we get into the details, it may be helpful to look at how one might implement a research project scaffolding model. I’ve provided a four-step process to guide you into getting the most out of the experience for you and your students:

- Choose a rigorous scaffolding model that connects to essential thinking skills, but is easy to use and flexible. I’m about to show you an example of one that I use.

- Understand the model until it becomes second nature. By doing this, the teacher will become confident in adapting elements of the model as required, also allowing for immediate differention if needed.

- Consider the time it will take for students to become familiar with the new model. You may wish to consider the big picture, as well. Will it be implemented on a class-by-class basis or implemented school-wide?

- Learn of ways (or develop your own) in which the various stages of the model can be made to come alive for students, or the ways in which key steps can be extended or expanded upon in interesting ways.

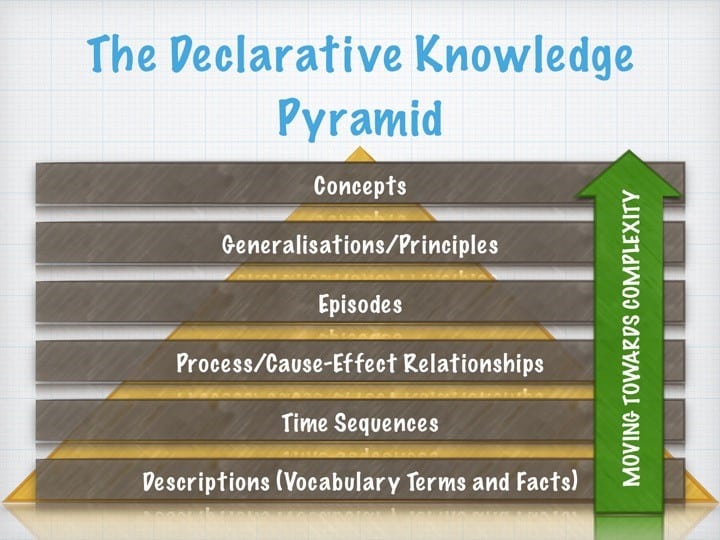

The model that I use for scaffolding research projects comes straight out of the Dimensions of Learning Framework (Marzano and Pickering et al., 2006). Dimension 2 of the framework looks at two areas of knowledge, classified as “Declarative Knowledge” and “Procedural Knowledge”. The one we are interested in is the declarative knowledge model. We could call it the Declarative Knowledge Taxonomy, but we could also refer to it as the Knowledge Pyramid. I’ve designed a graphic that shows this hierarchical structure quite clearly (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Declarative Knowledge Pyramid, based on Dimension 2 of the Dimensions of Learning Framework (Marzano and Pickering et al., 2006)Because this model is hierarchical, in that it progressively moves towards the more complex elements of thinking and knowledge, it is really useful as a scaffold for student exploration and research. By following the scaffold from the bottom up, you can start students off on a fact hunt, maybe involving some vocabulary exploration as well.

As students become more familiar with the various elements of the scaffold, they will start to research more complex types of information. You can also work from the top down, as in you might want students to think about the “big ideas”, the concepts that are significant to the topic of research. Doing this once in a while throughout the research process is helpful, as it gives students a focal point that directs where they are headed.

The model is also flexible, because you don’t have to use every element every time. For a younger cohort, you may scale it back, and for older students, you might focus less on facts and timelines and more on episodes, processes and concepts.

By the way, I rarely use the “generalizations and principles” in class, but you can choose to do so if it suits your purposes. The goal today is not really to get fully familiar with each element of the taxonomy. This is a kind of introduction to the model. Before we finish, though, it might be useful to briefly examine one element here.

The “Process” class of knowledge can be used in some fun ways. I sometimes get my students to come up with a process related to their topic that is really “big picture” or globally significant in some way. It’s often hard to find information at first, but as students begin exploring the idea of a process, they begin to see how useful processes are.

For my classes, depending on the topic of research, we’ve looked at processes such as “How to keep our beaches environmentally friendly”, or “How to manage heart disease”. These kinds of processes are relevant to say, a research project on surfing and the tourism industry, or global health issues.

Processes normally begin with “How to”. Coming up with a process, which could be expanded into a fully-fledged procedural text, is helpful for developing thinking skills because it gets students to think outside the box.

You can get your students to imagine how they might think if they were in the position of influence, such as the government of a country or the WHO, responsible for making decisions about how to manage certain diseases or prolonged drought, for example.

Hopefully this has given you a taste of some of the exciting things you can do in the PBL classroom, or while running a research project task. You may have a set question for your class from the outset, but sometimes it is fun to see where things head in a more open-ended research task.

Either way, the scaffold can be used to help students structure the research process, and more importantly begin to think in a variety of ways that will be helpful for good quality research and exploration. Next time, we’ll focus on some other elements in more detail and look at how these can be made to come alive in the inquiry-based classroom.

Further reading:

Allison, P., Gray, S., Sproule, J., Nash, C., Martindale, R. & Wang, J. (2015) Exploring Contributions of Project-based Learning to Health and Wellbeing in Secondary Education. Improving Schools 18(3) pp.207-220.

Bell, S. (2010) Project-Based Learning for the 21st Century: Skills for the Future. Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas 83(2) pp.39-43.

Buck Institute for Education Website: http://www.bie.org with information on PBL

Buck Institute for Education (2013) Research Summary: PBL and 21st Century Competencies . Avalaible at: http://www.bie.org/?ACT=160&file_id=542&filename=FreeBIE_Research_Summary.pdf .

Kokotsaki, D., Menzies, V. & Wiggins, A. (2016) Project-Based Learning: A Review of the Literature. Improving Schools 19(3) pp.267-277.

Lam, S., Cheng, R. & Choy, H. (2010) School Support and Teacher Motivation to Implement Project-Based Learning. Learning and Instruction 20(6) pp.487-497.

Larmer, J. (2015) Project-Based Learning vs. Problem-Based Learning vs. X-BL . Available at: https://www.edutopia.org/blog/pbl-vs-pbl-vs-xbl-john-larmer

Marzano, R., Pickering, J., Arredondo, D., Blackburn, G., Brandt, R., Moffett, C., Paynter, D., Pollock, J. and Whisler, J. (2006) Dimensions of Learning Teacher’s Manual. 2nd ed. Victoria, Australia: Hawker Brownlow EducationContributing Author:

Laurence Lee is a teacher and a linguist from Australia now living in Shanghai, learning the ropes of being a member of the global community. His passion is in literacy and communicative fluency of all shapes and sizes. Currently teaching English and ESL at Shanghai Singapore International School, Laurence has a linguistics major (BA degree) from the University of Adelaide and a teaching Grad. Dip. from Charles Darwin University. He has a black belt, along with a humble string of gold medals.

FariaPD supports teachers and leaders around the world with hands-on, active and creative professional development experiences. Join one of our online or in-person professional development events, each designed to support the unique goals of your school or district. FariaPD is part of Faria Education Group, an international education company that provides services and systems for schools around the world including ManageBac, a curriculum-first learning platform, OpenApply, an online admissions service, and Atlas, a tailored curriculum management solution for schools.