Written by Kelly McCurdy, Atlas Team

Like many earnest educators, I spent March of 2020 scouring the internet for reputable best practices for teaching in a completely virtual classroom. I hoped to pivot to what my region called “comprehensive distance learning” with the least amount of disruption and with the highest efficacy I could, as we all did. But virtual schools had been on the educational landscape for a while at this point. Although an uncommon option, I thought for sure that there would be at least a small bank of contemporary resources or studies providing data about effective strategies available for effectively teaching students online. Even though virtual schooling was not emphasized in my teacher preparation program, I was sure I could adapt quickly to this new learning environment.

The returns of my research were insufficient at best. Experienced educators were stepping up to share insights about their successes and challenges, but rigorous studies about how to effectively map curriculum, teach and assess, all in a virtual setting, were sparse. After two years, our inadvertent participation in this great virtual school experiment has spurred a wealth of action research and large-scale studies alike. We finally have data on effective strategies for curriculum and instruction online that we can review and discuss.

In large part, the research has concluded what many teachers discovered organically as we experimented with live classroom meetings in virtual classrooms and created lessons for our students to complete on their own: neither synchronous nor asynchronous learning in isolation is the answer, but instead a combination of the two strategies. Time to come together as a group is paramount for building relationships between teacher and student, creating a community in the class, and processing information through discussion, and more. However, learners require time to independently process information and focus their learning and express their ideas, or simply work through a practice or application task assigned to them.

During those early days of distance learning, my colleagues and I found ourselves falling into the trap of simply trying to recreate our brick and mortar classrooms in a virtual setting. I also found myself only superficially applying my SAMR training, neglecting opportunities to extend and redefine the classroom experience by going virtual, but instead trying to duplicate it in a way that simply wasn’t translating. The research-based approach is a more intuitive one: When designers of learning (regardless of age) consider each engagement opportunity, whether with content, each other, or the teacher/facilitator, we can determine whether a synchronous or asynchronous task is most appropriate.

Researchers investigating the topic of virtual learning have come to the same conclusions in their analysis of professional learning and development for educators: the most effective virtual professional development is not a singular synchronous session, nor is it a series of entirely asynchronous courses. It is a blended model which intentionally applies synchronous and asynchronous strategies intentionally to promote efficacy, accountability and differentiation. Professional development underwent the same virtual revolution as classroom teaching and has seemed to continually embrace the virtual setting even as students return to the classroom. While Zoom fatigue is a real phenomenon, schools are beginning to see and grasp the potential in virtual professional development for (and often by) their faculties that are not entirely dependent entirely on video conferencing.

Below are two contemporary blended professional development models from Zimmer and Matthews (2022) which apply best practices to maximize the opportunities of synchronous and asynchronous learning.

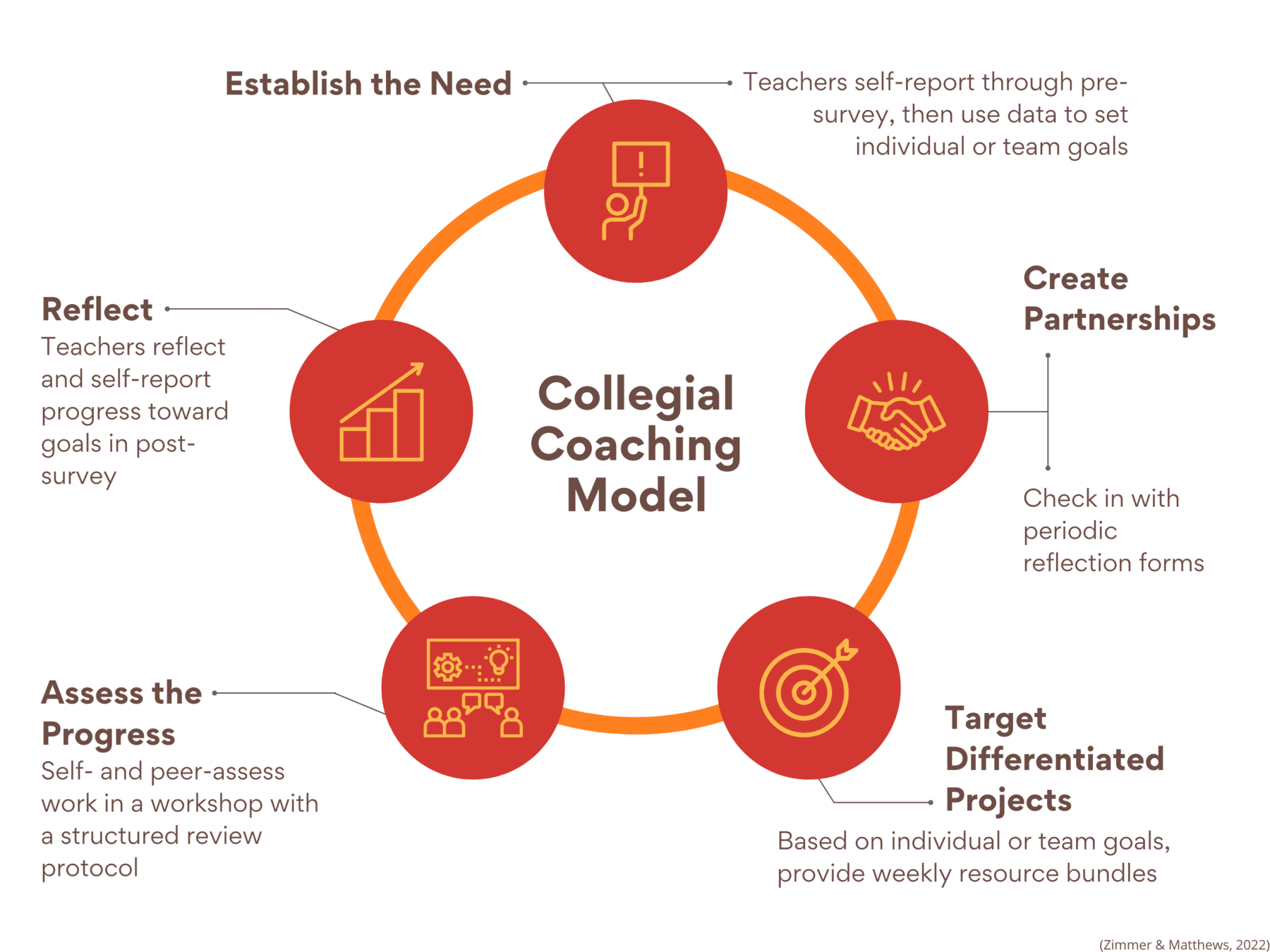

The Collegial Coaching Model

First is the Collegial Coaching Model, a cyclical process that relies on a virtual pre-assessment survey, ongoing virtual assessments, differentiated projects, and reflections all done virtually; the only synchronous component is workshops or structured peer reviews of the work generated by teachers on projects created based on individual or team goals.

The cycle created in this Collegial Coaching Model is one that can be facilitated by an outside specialist, or by various levels of leadership and faculty. What makes this model interesting is it reduces synchronous meeting times to only one phase of the cycle, as it is the only phase which requires participants to interact with each other in a live setting. All of the other phases involve participants interacting with the content and interacting 1:1 with the facilitator, both of which can be done asynchronously, meeting many of the needs of the busy educator.

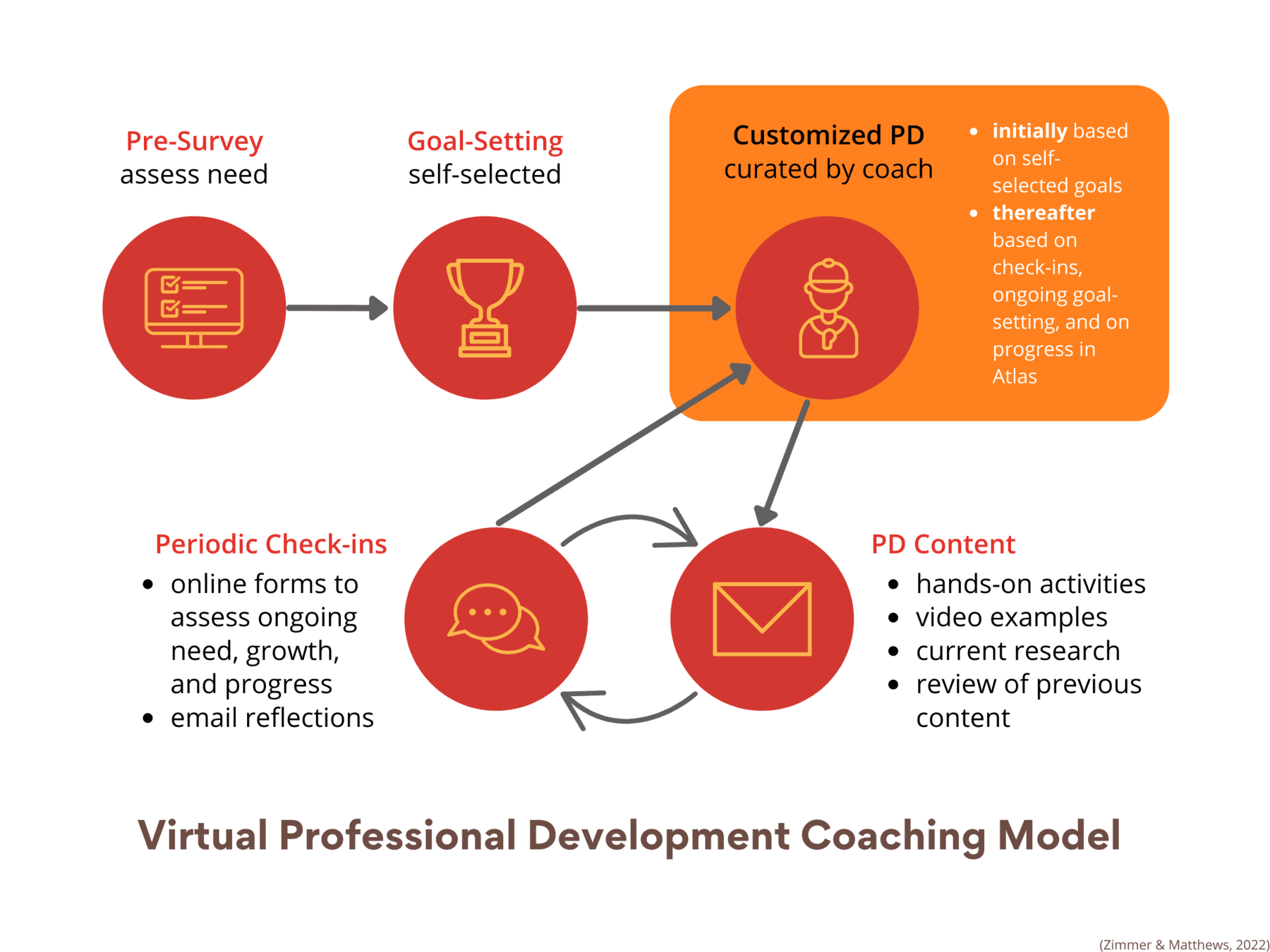

The Virtual Professional Development Coaching Model

Next is the Virtual Professional Development Coaching Model. This model is similar to the Collegial Coaching Model in that it relies heavily on asynchronous virtual engagement, beginning with a pre-assessment and an independently goal-setting assignment. The biggest difference between the two models is that the latter proposes a potentially entirely asynchronous model. But key to either a blended or asynchronous model is a relationship with the coach, customized PD content, and periodic check-ins.

This model also creates a flexible option that can be facilitated by PD specialists and individual schools as well. This version does challenge the conclusion that a blended model is best, in that it does not explicitly include synchronous meetings for workshops or peer review opportunities, but it also includes the flexibility to examine and determine which, if any, phases are best suited for a synchronous meeting.

As it becomes more and more apparent that virtual professional learning and development for educators are going to be long-term solutions in education, it is crucial for schools to intentionally structure these opportunities so that they accommodate the full schedule of an educator and provide the freedom for educators to both meet their goals in improving practice and nurture themselves as academics. At Atlas, we want to provide professional development that accomplishes these goals and look forward to creating a plan that can serve your individual teachers’ learning and meet the goals of the school as a whole.

References

Zimmer, W. K., & Matthews, S. D. (2022). A virtual coaching model of professional development to increase teachers' digital learning competencies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 109, 103544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103544

About The Author

Kelly McCurdy is a Professional Development Content Specialist with Faria Education Group, based in Portland, Oregon. She consults with educators domestically and internationally facilitating conversations about curriculum development and pedagogy. Kelly's first experience in education was teaching secondary Humanities, and has since supported public schools as lead teacher, committee chair, and program director. Kelly earned her Bachelor of Arts in English and her Masters in Teaching from Washington State University.